In this installment of the Teacher’s Corner, we discuss the latest news surrounding a renewed push to ensure early reading instruction is aligned with the science of reading. This includes the recent review of Units of Study by Student Achievement Partners and their report that the program lacks alignment with research. Finally, we share our own recommendations for supplementing Units of Study with evidence-based practices and helping educators conduct their own reviews of reading programs and practices.

Last month, Student Achievement Partners (SAP), a nonprofit educational consulting group, launched a new initiative to commission literacy experts to review reading programs in an effort to highlight research-based practices that should be used in every elementary classroom and help educators make sound decisions about curriculum. This project comes amid relatively stagnant reading scores (despite a large body of research that scientifically proves how children learn to read) and a renewed push for schools to adopt reading curricula and practices grounded in the ‘science of reading.’

SAP’s reviews will be conducted in partnership with expert reading researchers, who will evaluate programs against available research in the following areas: foundational reading skills, like phonics and fluency; text complexity; building knowledge and vocabulary; and supports for English learners.

The researchers released their first report on Lucy Calkins’ Units of Study program from the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project. Units of Study, more commonly known as “reading and writing workshop,” is one of the most widely used programs in the country, with 16 percent of teachers indicating they have used the materials in their classrooms, according to an Education Week Research Center survey. Expert reviewers noted the program’s strengths and weaknesses when compared to scientific evidence of how children learn to read. Overall, reviewers’ primary concern was that crucial aspects of reading instruction do not receive the necessary time and attention required to maximize student learning. This might be particularly problematic for children who are not well primed to read or who are not already reading when they enter school. (Note: The Teachers College Reading and Writing Project released a response to the SAP report in defense of the balanced literacy and the Units of Study program.)

Specifically, the SAP reviewers noted that the program

- provided insufficient time to acquire phonics skills;

- made frequent recommendations for use of the SMV (structure/meaning/visual system—widely known as the three-step cuing system), which contradicts a large body of research;

- provided insufficient guidance regarding how to use assessment results to inform instruction;

- lacked text that appropriately challenged or supported readers, preventing successful progress in reading;

- largely failed to build knowledge systematically and provided little guidance to teachers on word work to build vocabulary; and

- failed to adequately and sufficiently integrate explicit supports to support English learners.

Recommendations for Improving Literacy Instruction for Teachers Using Units of Study

Many educators will still be expected to use Units of Study as the primary curriculum until states or school boards have time to make official changes. Here, we offer some ways to supplement those lessons and other, similar “balanced literacy” curricula to maximize student learning.

| SAP Concerns about Units of Study | Possible Solutions | Helpful Resources (Sample lessons mentioned below can be adapted for other grades as needed.) |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient time devoted to phonics | Ensure teachers provide explicit and systematic phonics instruction, including instructional routines for teaching letter sounds, decodable words, sight words, and reading to reinforce learned sounds and words. Connect comprehension instruction so that phonics is not always taught in isolation. | Sample lessons and instructional routines for first grade Sample lessons and instructional routines for second and third grade |

| Use of the 3-step cueing system | Avoid the use of cuing systems and instead teach students to decode words by looking at all the letters in a word (see phonics recommendations above) | Guidance from Tim Shanahan |

| Lack of challenging texts and appropriate text reading supports | Although beginning readers (K-1) should read many texts at their instructional level to master basic decoding, more advanced readers should be provided opportunities to read texts with a range of difficulties. Support students before text reading by preteaching important vocabulary, setting a purpose for reading, and helping students decode when they make errors. Ensure students read a mixture of narrative and nonfiction books. | Sample “Daily Reading Routine” and lessons for second grade |

| Lack of knowledge building and vocabulary instruction | Provide explicit vocabulary instruction of essential words (i.e., 2–3 words critical to understanding the text) prior to reading by providing a student-friendly definition, visual, sample sentence, and examples. Aim to help students understand the “core meaning” of the words and the “shades” of meaning (e..g, bravado is a bit different from brave). Integrate multiple practice opportunities by having students use vocabulary words in discussion, reading, writing, brief games, and other engaging activities. Embed instruction on morphemes, root words, prefixes, and suffixes so that students learn how to derive the meanings of unknown words on their own. | Academic Word Routines in lesson plans for fourth grade |

| Inadequate English Leaner supports | Ensure ELs receive explicit and systematic instruction in phonics (see above), decoding, and encoding Build students’ vocabulary and conceptual knowledge (see explicit vocabulary instruction above). Provide opportunities for peer conversations so students practice using academic vocabulary. | Reading Tip Sheets for Educators |

Calls to Action

Given the recent media attention, schools and districts are beginning to ask themselves if the reading curricula they’ve selected is, in fact, rooted in reading science. We encourage educators to conduct their own reviews to ensure the reading programs being used will address the learning needs of most students and are aligned with research.

- Read the Executive Summary, if not the full report.

- Consider the extent to which your school or district’s early reading program is aligned with the science of reading.

- For instance, if you are currently implementing a “balanced literacy” program, “some of the research findings in this report will apply and others may not.”

- To learn more about the critiques of the balanced literacy or whole language approach to reading instruction, read this report from the Fordham Institute.

- Learn more about effective reading instruction from books identified as exemplary by the National Center on Teacher Quality (NCTQ).

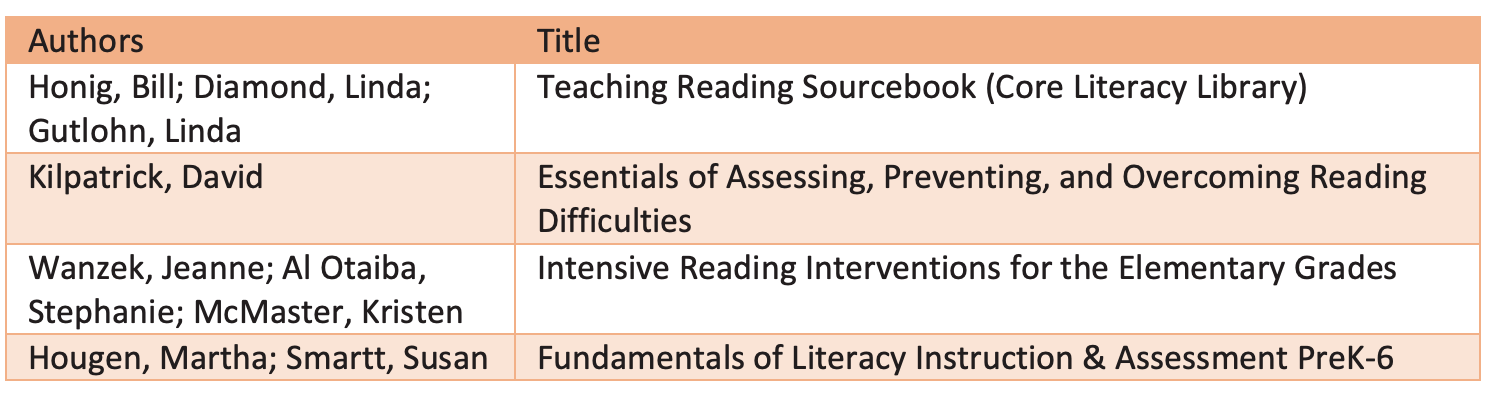

- The following texts are grounded in the science of reading and will be helpful to teachers aiming to provide evidence-based reading instruction. You can download the NCTQ report for more information.

- Download instructional materials aligned with the science of reading from trusted organizations, such as:

- The Texas Center for Learning Disabilities

- Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk

- The Florida Center for Reading Research

- Iowa Reading Research Center

- Lead for Literacy

- IRIS Center

- National Center on Intensive Intervention (see their literacy resources)

- Keep up with the latest on the science of reading.

- Follow us, TCLD, on Twitter and Facebook

- Follow Emily Hanford, education reporter at APM Reports, on Twitter.

- Read Sarah Schwarz’s reports at Education Week