Nugiel, T., Roe, M. A., Taylor, W. P., Cirino, P. T., Vaughn, S. R., Fletcher, J. M., Juranek, J., & Church, J. A. (2019). Brain activity in struggling readers before intervention relates to future reading gains. Cortex. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2018.11.009

Summary by Tehila Nugiel and Dr. Jessica A. Church

Overview

Reading is a life skill necessary for academic achievement; success with reading helps to propel individuals into successful adulthood. Interventions and remedial programs designed to address reading difficulties vary widely in approach and scale. Despite the general effectiveness of some interventions at the classroom or group level, individual student response to intervention is varied and can be difficult to predict. There is a growing interest in understanding a child’s intervention response using brain data coupled with behavioral measures to better categorize reading deficits and identify relations between brain and behavior before or after skill improvement (e.g., Barquero et al., 2014). Previous work has found patterns of brain activity and structure that have been proven useful for early identification of pre-readers at risk for reading difficulties. However, few studies have related brain activity to a child’s propensity to respond to reading intervention. A better understanding of this relationship could allow for improved classification and assignment to interventions for struggling readers.

This article by Nugiel and colleagues (2019) examines brain activity related to changes in reading skill in a group of fourth- and fifth-graders with comprehension reading difficulties. Fourth grade represents an important period in reading development when reading comprehension becomes crucial for learning and individuals who struggle with reading comprehension are in danger of falling behind in many subjects. A major focus of the work was finding patterns of brain activity that related to how much a struggling reader would respond to later reading instruction. The authors were interested in brain regions that are typically engaged for reading, as well as those supporting executive control. Executive control processes are higher order cognitive processes that include keeping information in mind, planning, and inhibition (Diamond, 2013). Previous work has shown that executive control skills are related to a range of reading skills, from single word reading to reading comprehension. To test for the relationship between brain activity and changes in reading skill, at the beginning of the school year, a whole cohort of fourth-graders underwent screening for reading difficulty with a reading comprehension measure. Students identified as struggling readers were assigned to one of two in-school reading interventions.

A subset of struggling readers voluntarily participated in fMRI scans before and after a 16-week daily in-school reading intervention. In the fMRI scanner, the students did two tasks: sentence reading and an executive control demanding but nonreading task (a stop-signal task). For the reading task, students were presented with sentences to read and they used a button to indicate whether or not the sentence “made sense” to activate reading and control brain regions. The stop-signal task tapped into control and motor inhibition brain processes. A group of nonstruggling readers in the same grades did the same scanner tasks and served as a comparison group.

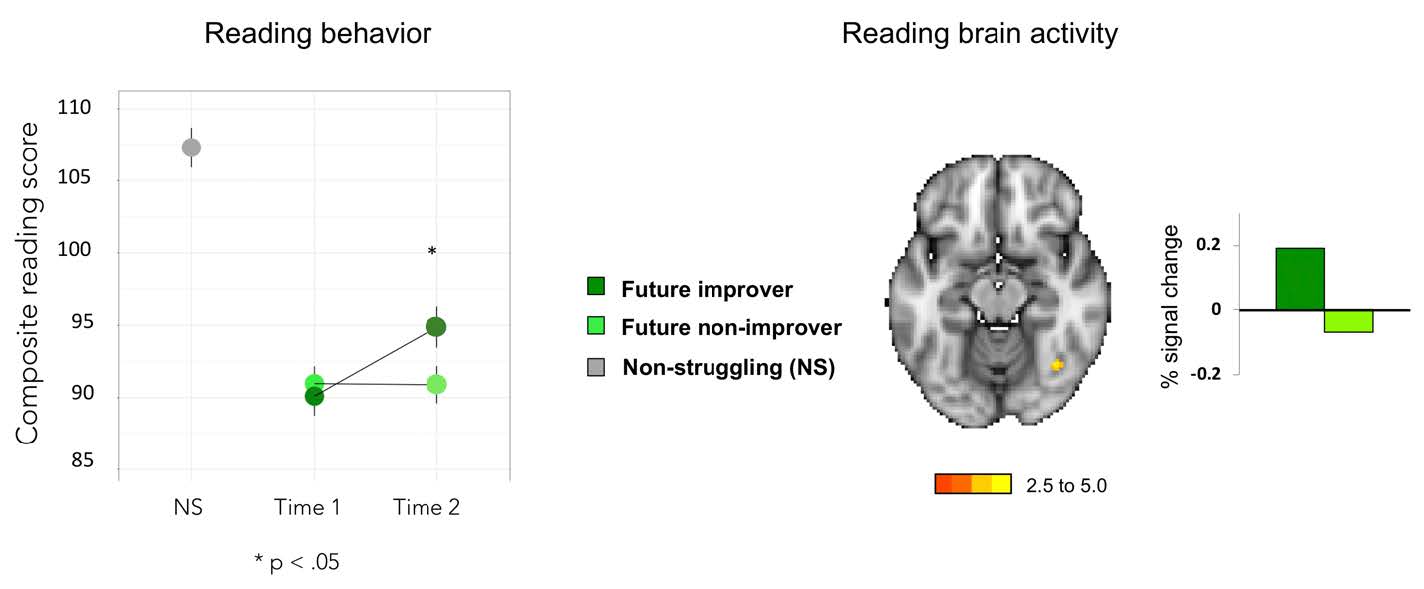

Along with the fMRI scanning, struggling readers had their reading tested before and after the 16-week intervention period. To test for brain responses that may relate to better response to intervention and gains in reading skill, the authors calculated the differences between reading skill before intervention and reading skill after intervention. This change in reading skill was used to sort the struggling readers into groups of improvers (those who saw sizeable gains in their reading) and nonimprovers (those who saw small changes or no changes in their reading). These labels were then used to sort the brain data collected before instruction. The authors tested for differences in brain activity between these two groups and between each group and the nonstruggling readers. The time period before intervention was interesting to test for brain differences because the improver and nonimprover participants were not different on their pre-intervention measures of behavior. These group differences were tested across the whole brain, in both tasks, with a particular interest in both reading and executive control brain systems.

Key Findings

Brain activity in reading and executive control brain systems before intervention differed between improver and nonimprover groups. Improvers and nonimprovers looked virtually the same behaviorally, however there were differences in brain activity before any intervention. Activity in several regions across the brain showed differences related to later gains in reading skill. In the reading system, improvers had more brain activity than nonimprovers in the right ventral fusiform, a region thought to support processing letters and written text. Of interest, using fMRI data from after intervention, activity in this region continued to relate to reading gains.

Before intervention (pre) there were no differences in reading scores between struggling readers who go on to improve and those that don’t. Despite this, some brain activity in the right fusiform differed before intervention from those who would later gain in skills and those who wouldn’t.

There were also differences between the improver groups and nonstruggling readers in executive control brain regions. Nonimproved readers showed different levels of activity compared to nonstruggling readers in an executive control region in posterior lateral temporal cortex. This region is part of a network that is thought to support moment to moment shifts in attention. This finding suggests that beyond the reading system, the way struggling readers recruit other more general-use brain systems such as executive control systems is related to reading change over time.

Reader group differences were specific to the sentence reading task. The authors next asked whether the patterns of difference in executive control and task-general brain regions were specific to the reading process, or whether these effects would be seen in nonreading tasks as well. The authors did the same set of analyses comparing improver groups and nonstruggling reader’s brain activity during the stop-signal task. The authors found that while executive control systems were engaged for the task, there were no significant differences in brain activity between any of the groups. This finding suggests that it’s the way struggling readers recruit executive control systems for reading specifically that is driving group differences in brain activity. There were no differences between any of the reader groups in the way they engaged their brains for a nonreading but executive control-demanding task.

Implications of Study Findings and Implications for Future Research

Nugiel and colleagues set out to test whether brain activity measured before intervention could be helpful in understanding future changes in reading skill. They focused both on brain systems known to be recruited for reading, as well as executive control systems that support many attention-demanding processes, including reading. They found that brain activity before intervention differed between improvers and nonimprovers, while behavioral measures of reading did not differ between the groups at that timepoint. This result suggests that neurobiological measures can provide important information about variability among individuals with learning difficulties. Further studies pairing neurobiological measures with measures of reading ability and especially growth or change in reading ability are important for understanding why some struggling readers improve for a given intervention approach while others do not.

This study found that brain activity in executive control systems was related to changes in reading skill, but this relationship was specific to a reading-related task. The authors observed no general atypical patterns of executive control brain activity in the struggling readers. This suggests that while there is an important relationship between executive control and reading skill, this relationship could be quite nuanced. Interventions that attempt to change executive control in a broad way may not result in change to reading skill. Instead, weaving components of executive control directly into the reading process could be more beneficial for struggling readers. More research testing this idea is a next important step for understanding how executive control processes facilitate reading, and for improving interventions to support struggling readers.

References

Barquero, L. A., Davis, N., & Cutting, L. E. (2014). Neuroimaging of reading intervention: A systematic review and activation likelihood estimate meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083668

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive Functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 135–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750